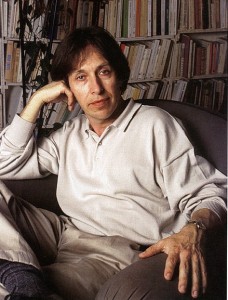

The French intellectual Pascal Bruckner casts a critical eye on happiness in his newly translated book, Perpetual Euphoria: On the Duty to Be Happy

The French intellectual Pascal Bruckner casts a critical eye on happiness in his newly translated book, Perpetual Euphoria: On the Duty to Be Happy. Much of what he has to say about happiness applies equally to health.

In the first post on this blog I asked: How did health, which used to be something we were born with, become something we believe we can personally control. Today most people in developed countries assume they can avoid certain diseases and prolong their lives by practicing a “healthy lifestyle.” How did this happen? When did the change occur? What does it mean that – unlike earlier generations — we’re so preoccupied with our health?

Attitudes towards both health and happiness changed in the sixties. In an interview in The Guardian, Bruckner comments: (emphasis added)

After the 60s, there is no more distance between one’s happiness and oneself. … One becomes one’s own main obstacle. To overcome this obstacle a huge market opened: medicine to modify your mood, surgery to modify your body, and it also includes the spread of therapy and new or reformed religions. So Jesus is no longer this transcendent God, but a life coach who helps you overcome addiction and so on. …

We should wonder why depression has become a disease. It is a disease of a society that is looking desperately for happiness, which we cannot catch. And so people collapse into themselves. …

[P]eople are very unhappy when they try hard and fail. We have a lot of power in our lives but not the power to be happy. Happiness is more like a moment of grace.

The relentless search for happiness makes people unhappy. Similarly, the pursuit of perfect health invites overdiagnosis. We label millions of healthy, asymptomatic individuals with a disease and proceed to treat them. Both the label and the treatment have adverse side effects that make us less healthy.

Invisible penitence

It’s only natural that we don’t question prevailing beliefs about health and happiness. Nearly everyone we interact with endorses and subscribes to the view that health and happiness are attainable goals if only we discipline ourselves sufficiently. Especially loud are the voices of those with a financial interest in our continuous pursuit of these goals.

It’s helpful, then, to have a countervailing voice like Bruckner’s. Here’s an excerpt from the introduction to his book – available online as a PDF. (emphasis added)

[F]or our young people, this privilege [to be happy] quickly comes a burden: seeing themselves as solely responsible for their dreams and their successes, they find that the happiness they desire so much recedes before them as they pursue it. Like everybody else, they dream of a wonderful synthesis that combines professional, romantic, moral, and family success, and beyond each of these, like a reward, perfect satisfaction. As if the self-liberation promised by modernity were supposed to be crowned by happiness, as the diadem placed atop the whole process. But this synthesis is deferred as they elaborate it, and they experience the promise of enchantment not as a blessing but as a debt owed a faceless divinity whom they will never be able to repay. The countess miracles they were supposed to receive will trickle in randomly, embittering the quest and increasing the burden. They are angry with themselves for not meeting the established standard, for infringing the rule. …

[W]e are never sure that we are truly happy. When we wonder whether we are happy, we are already no longer happy. Hence the infatuation with this state is also connected with two attitudes, conformism and envy, the conjoint ailments of democratic culture: a focus on the pleasures sought by the majority and attraction to the elect whom fortune seems to have favored. …

[W]e now tell ourselves a strange fable about a society completely devoted to hedonism, and for which everything becomes an irritation, a torture. Unhappiness is not only unhappiness; it is, worse yet, a failure to be happy.

By the duty to be happy, I thus refer to the ideology peculiar to the second half of the twentieth century that urges us to evaluate everything in terms of pleasure and displeasure, a summons to a euphoria that makes those who do not respond to it ashamed or uneasy. A dual postulate: on the one hand, we have to make the most of our lives; on the other,we have to be sorry and punish ourselves if we don’t succeed in doing so. This is a perversion of a very beautiful idea: that everyone has a right to control his own destiny and to improve his life. How did a liberating principle of the enlightenment, the right to happiness, get transformed into a dogma, a collective catechism?

The supreme Good is defined in so many different ways that we end up attaching it to a few collective ideals— health, the body, wealth, comfort, well-being — talismans upon which it is supposed to land like a bird upon bait. Means become ends and reveal their insufficiency as soon as the delight sought fails to materialize. So that by a cruel mistake, we often move farther away from happiness by the same means that were supposed to allow us to approach it. Whence the frequent mistakes made with regard to happiness: thinking that we have to demand it as our due, learn it like a subject in school, construct it the way we would a house; that it can be bought, converted into monetary terms, and finally that others procure it from a reliable source and that all we have to do is imitate them in order to be bathed in the same aura. …

[H]appiness … is a Western idea that appeared at a certain point in history. There are other ideas—freedom, justice, love, friendship—that can take precedence over happiness. How can we say what all people have sought since the dawn of time without slipping into hollow generalities? I am opposing not happiness but the transformation of this fragile feeling into a veritable collective drug to which everybody is supposed to become addicted in chemical, spiritual, psychological, digital, and religious forms.

“I love life too much to want to be merely happy!”

Related posts:

The unavoidable and burdensome responsibility to be happy

Are married people happier? Are parents?

Self-help as psychological healthism

Self-help from Norman Vincent Peale to the new Oprah

The history of self-help: Some books to read

Pascal Bruckner on doctors and patients

Bruckner on the good life, money, and the unequal world of work

Bruckner on the family, being gay, and AIDS activism

DSM-5: A “wholesale imperial medicalization of normality”

Sex, lies, and pharmaceuticals

We’re all on Prozac now

Resources:

Image: Babelio

Pascal Bruckner, Perpetual Euphoria: On the Duty to Be Happy

Pascal Bruckner, Introduction, Invisible Penitence, Princeton University Press

Andrew Anthony, Pascal Bruckner: ‘Happiness is a moment of grace’, The Guardian, January 23, 2011

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.